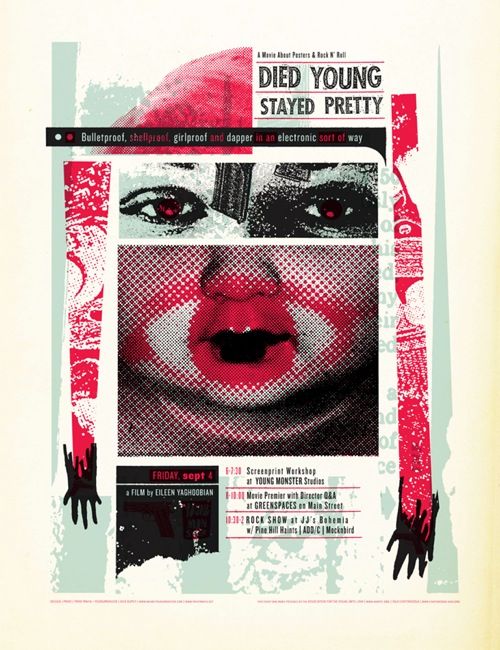

this poster will make me have nightmares. it is so creepy to me.

If you go through life free of bad habits, you won't live forever, but it will feel like it.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

By D.A. Blyler

It all starts one quiet afternoon at the brew-pub. I'm sitting with my associate Bobby, enjoying a pint of the house ale, when Stephen Covey (author of "The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People") suddenly appears on the bar television. I can't quite describe the level of annoyance that the bald business guru brings to a room of gentle drinkers, trying to enjoy themselves while the rest of the populace is at work, but a sudden wail from a man in the far corner, similar to that of a small dog yanked forcefully by the tail, alerts everyone that something is terribly wrong. In a matter of moments all eyes are fixed in distress upon the television.

Soon customers with clenched fists start to share horror stories of managers who force-fed Covey's book to them. And of group leaders who scurried around the office pasting up signs like: "Synergy!" or "Be Proactive!" or "What would Covey do in your situation?" Rage and desperation had finally forced our fellow drinkers to leave their professions and find solace in the thick, rich ales fermented by the pub's microbrewery.

Bobby and I are amazed. Having spent 10 years carving out lives as professional grad students, we've been oblivious to the rising tide of worker despair. I remember seeing a Covey infomercial several months back; it seemed harmless enough. Watching employees become automatons spouting Covey's catch phrases at every opportunity was the funniest thing I had seen on television in quite a while. But now, as the man in the corner begins weeping, Bobby and I realize that larger issues are at hand.

Covey is no business guru, but rather the result of a world gone awry -- the world of work made worthless. Gone are the large expense accounts. Gone are the smoke breaks and three martini lunches. Gone are the innocent office flirtations. Good lord, who would want to work in an environment like that?

I slam my fist on the table. "We need a book about the 7 Vices of Highly Creative People before the whole country ends up in a straitjacket!" Bobby agrees enthusiastically, grabs a stack of napkins and begins writing. All the years we've spent studying history and literature are finally paying off. It isn't easy. But after six hours and five pitchers we finish the job. The pub closes so we gather the napkins and head for a late-night bar to celebrate. It isn't quite a book, but what the hell. We have better things to do than write another damn self-help book.

Vice one: Be a drinker

Winston Churchill, a great fan of the martini, once said that it must always be remembered that he has taken more out of alcohol than alcohol has taken out of him. For Churchill, like many other great drinkers, alcohol was a tool used to feed creativity and social discourse. For others, like Ernest Hemingway, alcohol was a way to place the mind on a different plane after writing all day at a desk. This is what old Papa had to say:

I have drunk since I was 15 and few things have given me more pleasure. When you work all day with your head and know you must again work the next day, what else can change your ideas and make them run on a different plane like whiskey?

Some people might say that this is to use alcohol as a crutch, but that's always been the case. Mark Twain, who drank from morning until night, would periodically abstain from drink and smoke just to silence the critics who said he was a slave to his vices. And on his feistier days, he would give them a severe tongue-lashing. "You can't get to old age by another man's road!" he'd scream. "My vices protect me but they would assassinate you!" His critics would then shuffle away to their 12-step programs and the organizing of their sock drawers.

To be a drinker means, of course, to be social. Sure, it's all right to drink by oneself on occasion. But because the highly creative live so often in the private world of ideas, they also need to mingle with their friends at a good party. That's why F. Scott Fitzgerald threw his fantastic "Gatsbyesque" parties on Long Island, inviting such other besotted artists as Gloria Swanson, Sherwood Anderson, John Dos Passos and Dorothy Parker. Remember, though, that when entertaining the highly creative some ground rules need to be set. Fitzgerald's were posted at the entrance to his home in Great Neck:

Visitors are requested not to break down doors in search of liquor, even when authorized to do so by the host and hostess ... Weekend guests are respectfully notified that the invitation to stay over Monday issued by the host-hostess during the small hours of Sunday morning must not be taken seriously.

It's always good to think ahead.

Lastly, something should be said for the occasional weekend bender, that is as long as your head is in the right place. If a person is suppressing problems or going through severe emotional distress, alcohol can bring out bad tendencies ... like singing karaoke. But if you're secure with yourself, the occasional bender can be a rather helpful mystical experience. As Henry James once wrote, "Sobriety diminishes, discriminates and says no, while drunkenness expands, unites and says yes!"